Transformation

- Redefinition

- Tech allows for the creation of new tasks, previously inconceivable

- Modification

- Tech allows for significant task redesign

Enhancement

- Augementation

- Tech acts as a direct tool substitute, with functional improvement

- Substitution

- Tech acts as a direct tool substitute, with no functional change

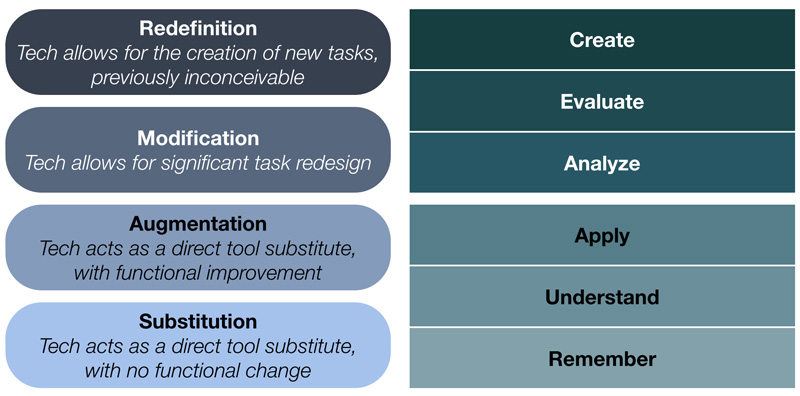

Figure 1. The SAMR Model as created by Dr. Ruben Puentedura (2015).

What are the four levels of SAMR?

The SAMR model is a hierarchy consisting of four levels of integrating technology in the classroom with each subsequent level increasing in its capacity for learning potential and student outcomes. The first two levels of Substitution and Augmentation provide an enhanced learning experience for students through the inclusion of technology while the upper levels of Modification and Redefinition are transformational in nature and allow for deeper connections, comprehension, and construction of knowledge by the student (Common Sense Education, 2016).

Substitution: Same Task, New Tool

The substitution level is the first step in the SAMR ladder. It requires “substituting” a new technological tool in place of a previously used tool to complete a task. The task is not fundamentally changed through use of this tool, which causes the student learning outcome to be virtually unchanged as well (Puentedura 2013).

An example of Substitution is using a word processing program such as Microsoft Word or Google Docs to compose a piece of writing versus using paper and pencil. Again, the task and the student learning outcome is the same with this act of substitution, although there may be some convenient advantages such as the amount of time required for completion, the ease of completing the task, and the digitization of student learning for assessment purposes (Portney 2018).

Augmentation: Same Task, Some Enhancements

Climbing up to the next level, Augmentation again consists of the use of a technological tool to complete a task normally accomplished without the assistance of the new tech. However, the Augmentation level enhances the learning experience by making use of functional improvements inherent to the chosen tool (Puentedura 2006).

Returning to the writing assignment example, Google Docs has built-in features such as a spell checking tool, a dictionary, as well as the abilities to cut and paste, save work instantly and access the work anywhere with an internet connection. Typically, Augmentation-level tasks result in some small but noticeable improvements in student learning outcome (Puentedura 2006).

Modification: Redesigned Task, Transformed Learning Experience

Crossing over from the enhancement levels of SAMR into the transformation levels involves rethinking and redesigning the task at hand through Modification. As Puentedura states, the “heart of the task remains the same,” but new educational objectives are made possible through the integration of the technological tool (Puentedura 2013).

The piece of writing each student would have been assigned might now become a collaborative writing assignment, with instant feedback made available through sharing and commenting features of programs such as Google Docs. To make the jump from Augmentation to Modification requires this alteration to the core task as opposed to a reproduction, resulting in significant improvements to the outcomes of students (Puentedura 2013).

Redefinition: New Task, Powerful Possibilities

The final and most impactful level of the SAMR model is Redefinition. Now, the use of technology allows for the possibility of completely new, “previously inconceivable” tasks, evolving the learning experience into a more comprehensive construction of knowledge by students (Puentedura 2013).

Maybe the composition assignment is now transformed into a multimedia presentation through the use of Google Slides or Prezi with the addition of audio, video, interactive links, and other aspects that better demonstrate a deeper understanding by the student. In addition, the Redefinition stage often includes students becoming authorities in a particular area, acting as peer mentors to their classmates or even a global audience. With more possibilities comes a greater potential for student voice and choice, providing opportunities for student ownership and exceptional achievements (The Brainwaves Video Anthology 2017).

How does SAMR relate to Bloom’s Taxonomy?

Many educators upon first encountering the hierarchical design of Puentedura’s SAMR model draw parallels to Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy. Both are structured in a similar fashion, with subsequent levels in SAMR increasing potential for student achievement and understanding while Bloom’s Taxonomy advances in the complexity of cognitive processes used during learning.

Often, educators can feel overwhelmed by the inclusion of a new framework to understand and implement in their curriculum, but these two models need not be in competition or conflict with each other. As educational and developmental psychologist Lindsay Portnoy posits, “Bloom’s taxonomy is essential for teachers to identify student’s levels of thinking, whereas Puentedura’s taxonomy is essential for teachers to identify the tools that can be used to innovate on instruction” (2018). Using these models in partnership with each other is a powerful way to combine pedagogy and technology.

Puentedura has made correlations of his four levels SAMR levels to Bloom’s six levels of understanding, as illustrated in Figure 2. The key relationship to this diagram exists in connecting Bloom’s Remember, Understand, and Apply with the Enhancement levels of SAMR and Analyze, Evaluate, and Create with the Transformation levels of SAMR (2014a).

Figure 2. The SAMR Model as it relates to Bloom’s Taxonomy, created by Dr. Ruben Puentedura (2014a).

Another commonality between the two frameworks is that each has received their share of criticism on ranking some skill or task as preferable to the lower levels. Critics of Bloom’s Taxonomy note the implications set forth by the diagram in that the lower levels of cognitive processes such as Remember and Understand are not complex or worthy enough tasks for a student or educator’s time (Lawler 2016). Similarly, there occur interpretations of the SAMR model that also challenge the value the model seems to put on Redefinition as the preferred pathway over Substitution in all scenarios (Takizawa 2015). To this, Puentedura says, “SAMR is not intended to make value judgments,” and encourages educators to determine their learning goals and comfort level when working with technology, keeping in mind that increased outcomes can be expected at the transformative levels of SAMR (McQuade 2015).

The comparison of SAMR with Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy can be a helpful tool for understanding how two prevalent frameworks can complement each other with the goal of structuring the most effective, engaging student learning environment while providing scaffolding for educators to utilize in their practice. However, this association, according to Puentedura, is not a “necessary” interrelation to consider, as varied examples of Create-level tasks can make use of Substitution or Augmentation while Remember-level tasks might be used for Redefinition purposes (2014a).

What are important things to keep in mind when working with SAMR?

Knowing the inherent value of each individual level of the SAMR model is key to understanding its full potential of use in the classroom. The Substitution and Augmentation levels can prove to work well for particular tasks, especially as a sort of introduction to an educator just starting to develop their use of technology (Puentedera 2006). Again, it is in moving beyond these levels that educators have the potential to see a more significant increase in student outcomes. The imagery of the ladder works well here, with each level an important piece that can be built upon to reach greater results.

An oversight that can occur when beginning to use SAMR is to get caught up in focusing on the technological tool instead of the desired student outcome. Rather SAMR is meant to keep the student learning, objectives and learning process at the core while the technological tool provides a means of information and support (Holland 2014). Again, Portnoy states, “A single tool, even with the greatest AI, will never be a panacea for education. But technology does help teachers take learners to worlds beyond their imagination while making learning visible and actionable” (2018). Puentedura maintains that it is a mistake to start with the technology and move to the task and sees the most important piece as the “pedagogy-content” connection to guide the path to greater student achievement (McQuade 2015).

How do I get started using SAMR in my teaching?

As stated above, the “ladder” structure of SAMR provides an intuitive method for incorporating Puentedura’s principles. Starting with the Substitution and Augmentation of tasks that the educator is already comfortable assigning to students allows for a time and space for experimentation from which to eventually build up to more transformative levels (OETC 2014).

Beginning to align the SAMR model with a unit of study can be daunting. Puentedura suggests three approaches to picking a unit to start with: find a unit of study the educator is passionate about, one that has proven to be a challenge to students in the past, or an area that will be of particularly good interest for students to master for future endeavors (Puentedura 2014b).

Another recommendation he gives is to collaborate with other teachers to dig into the model and plan out how to apply it to a unit. This may start with a discussion from educators of the same content area, but Puentedura encourages to eventually branch out to sharing conversations with those of differing grade levels or subjects to acquire a variety of examples to draw upon (McQuade 2015). Evan Tobias of Arizona State University echoes this recommendation of collaboration when planning comprehensive projects, adding that inquiring with students, tapping into their interests and wonders could help in designing the learning process (2016, p. 128). As with students, a growth mindset is vital for any new undertaking as not everything works as planned. Although the risk is greater at the upper levels of SAMR, any missteps at the Modification and Redefinition stages provide opportunities for growth in teaching practice and a place from which to build to higher levels of student outcome (Common Sense Education 2016).

References

- Common Sense Education. (2016, July 12). The impact of the SAMR model with Ruben Puentedura. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SWU0Dzz6gs0

- Holland, B. (2014, February 25). In response to “redefinition”. [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://brholland.wordpress.com/2014/02/25/in-response-to-redefinition/

- Lawler, S. (2016, February 26). Identification of animals and plants is an essential skill set. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20161117044125/http://theconversation.com/identification-of-animals-and-plants-is-an-essential-skill-set-55450

- McQuade, P. (2015, May 5). Ruben Puentedura - SAMR. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CgyNKsnuBB4

- OETC. (2014, April 28). Dr. Ruben Puentedura | Spark PDX 2014. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qN4J6AfbpbA

- Portney, L. (2018, February 1). How SAMR and tech can help teachers truly transform assessment. Ed Surge. Retrieved from https://www.edsurge.com/news/2018-02-01-how-samr-and-tech-can-help-teachers-truly-transform-assessment

- Puentedura, R. (2006, August 18). Transformation, technology, and education. [Html of slides combined with audio]. Retrieved from http://hippasus.com/resources/tte/part1.html

- Puentedura, R. (2013, January 7). Technology in education: A brief introduction. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rMazGEAiZ9c

- Puentedura, R. (2014a, September 24). SAMR and Bloom’s Taxonomy: Assembling the puzzle. Common Sense Education. Retrieved from https://www.commonsense.org/education/blog/samr-and-blooms-taxonomy-assembling-the-puzzle

- Puentedura, R. (2014b, December 11). SAMR and TPCK: A hands-on approach to classroom practice. [PDF file]. Retrieved from http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2014/12/11/SAMRandTPCK_HandsOnApproachClassroomPractice.pdf

- Puentedura, R. (2015, April). Contextualizing SAMR. [PDF file]. Retrieved from http://hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2015/04/ContextualizingSAMR.pdf

- Takizawa N. (2015, June 7). TPACK or SAMR or both?. [Blog Post] Retrieved from https://nicolatakizawa.coetail.com/2015/06/07/tpack-or-samr-or-both/

- The Brainwaves Video Anthology. (2017, October 28). Ruben Puentedura - Rethinking educational technology. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7N67bt0FA8s

- Tobias, E.S., (2016). Digital media and technology in hybrid music. In C. R. Abril, & B. M. Gault (Ed.), Teaching general music: Approaches, issues, and viewpoints (pp. 112-140). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.